Scroll for the English version of the following speech about the exhibition which was written and presented by Katrin Seglitz at the opening.

Katrin Seglitz

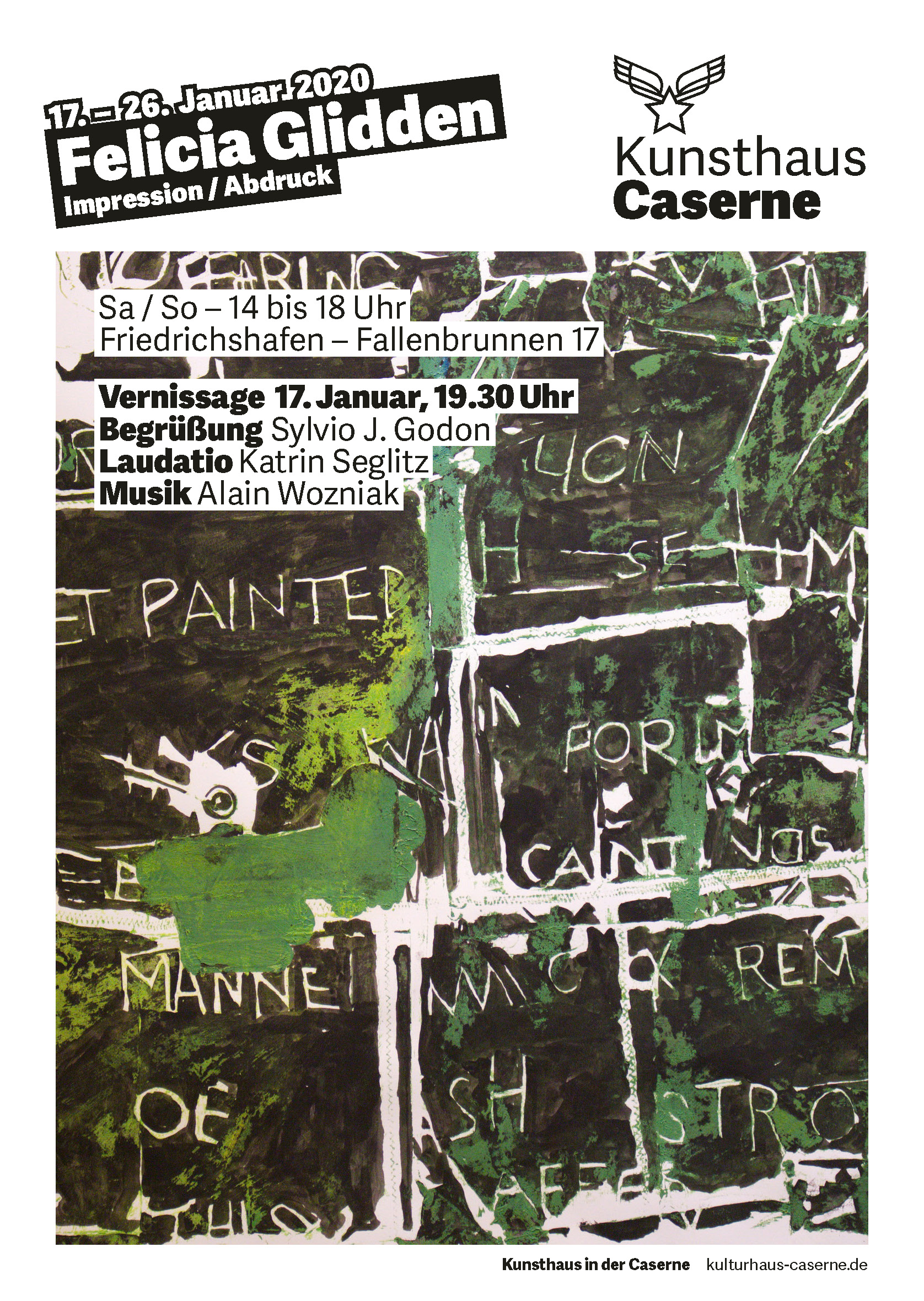

Rede für die Vernissage der Ausstellung „Impression/Abdruck“ von Felicia Glidden am 17.1.2020

im Kunsthaus Caserne in Friedrichshafen Fallenbrunnen

Wenn man in diesen Raum kommt, ist man beeindruckt von den großformatigen Arbeiten, die hier hängen. Impression/Abdruck hat Felicia die Ausstellung genannt, und beide Wörter haben einen Hof von Bedeutungen: In der Impression hören wir die Presse, das Pressen, den Druck, das Drucken und Drücken und Eindrücken. Begriffe, die mit Druck und Druckverfahren zu tun haben. Und der Frage, was einen Eindruck hinterlässt.

Diese Frage stellt sich Felicia, dieser Frage geht sie experimentell mit ihren Arbeiten nach, der Frage, was sie beeindruckt, so beeindruckt, dass sie nach einem Ausdruck dafür suchen muss.

Sie ist in Minneapolis aufgewachsen und hat in der Stadt gelebt bis sie 18 war. Danach ist sie zum Studium nach Duluth gegangen. Sie hat Mathe und Ingenieurwesens studiert und Kurse belegt in Visual Art und Dance. Duluth liegt am Oberen See, einem der drei riesigen Seen im Norden der USA, an der Grenze zu Kanada.

Duluth hat einen großen Hafen, von hier aus fahren Schiffe über den Sankt-Lorenz-Seeweg bis in den Atlantik. Rohstoffe werden in Duluth verschifft: Eisenerz, Getreide, Kohle, Öl und Holz. Die Stadt selbst ist mit 86 000 Einwohnern keine große Stadt, nur wenig größer als Friedrichshafen.

In ihrem 3. Studienjahr hat sich Felicia ganz der Kunst zugewandt.

Sie zog in ein altes Holzhaus mitten im Wald, in der Nähe des Sees, eine Stunde von Duluth entfernt. Sie hat sich in der Garage ein Atelier eingerichtet, mit Holz geheizt, Kunst gemacht und das Geld, das sie zum Leben brauchte, mit der Renovierung von Häusern und Booten verdient. Sie hat in der Natur und mit der Natur gelebt, eine Erfahrung, die sie bis heute trägt. Und prägt.

Womit wir wieder beim Druck sind und beim Eindruck, den etwas hinterlässt. Noch bevor sie die Mülltrennung in Deutschland kennengelernt hat, hat sie, als sie im Wald lebte, den Müll getrennt. Seit zwei Jahren sind die Verpackungen mehr und mehr in den Fokus ihrer Aufmerksamkeit gerückt.

Auch Verpackungen werden entworfen und hergestellt. Sie dienen dem Schutz von Lebensmitteln und Produkten. Werden geöffnet oder aufgerissen, abgerissen und entfernt. Sie haben eine dienende Funktion, werden in der Regel übersehen.

Felicia macht sie sichtbar, indem sie Kartons auseinanderklappt, unter Papier legt und mit Grafit darüber reibt, so dass ein Abdruck entsteht. Sie hat aufgeklappte Kartons und Verpackungen zusammengenäht. Und aus Plastiktüten Trashquilts gemacht.

Anfangs wurde die Entdeckung der Herstellung von Kunststoffen gefeiert. Der Erfolg führte zu massenhafter Produktion. Längst fühlen wir uns bedrängt und bedroht durch die Flut von Plastik in jeder erdenklichen Form.

Und doch gibt es Kunststoffe, von denen wir uns wünschen, dass sie uns überleben. 1856 wurde Zelluloid entwickelt, ab 1870 vermarktet und weiterentwickelt als Trägermaterial für Filme. 1951 wurde die Herstellung eingestellt, denn Zelluloid ist leicht entzündlich. In trockener Umgebung sinkt der Wassergehalt und Zelluloid wird zum Sprengstoff, der sich spontan entzünden kann.

Zelluloid wurde ersetzt durch eine mit einer Fotoemulsion beschichteten transparenten Folie aus Tri-Acetat oder Polyester. Streifen aus dem Zeitalter analoger Fotografie finden sich noch in vielen Haushalten. Auch bei Felicia.

Als der Keller von Felicia und Alain bei einem Hochwasser überflutet wurde, wurde klar, dass auch Tri-Acetat und Polyester verdirbt, wenn es nass wird. Die Dias in ihrem Archiv zeigen neben den festgehaltenen Augenblicken auch abstrakte Landschaften von sich ausbreitendem Schimmel. Felicia hat aus den zerstörten Fotos eine memory skin gemacht, eine Erinnerungshaut. Und sie zu einer Allegorie der Vergänglichkeit gemacht.

Felicia: „Die Zeit ist wie eine Flut, die das, was mal Gegenwart war, überzieht und ausbleicht.“

Kunststoffe dienen der Verpackung, dem Schutz von Dingen, aber auch als Träger von Erinnerungen. Felicia geht es in dieser Ausstellung darum, ihre Materialität sichtbar zu machen und die Formen, die im Umlauf sind.

Das ist der eine Aspekt, der eine Teil ihrer hier ausgestellten Arbeiten. Der andere Aspekt ist das Sichtbarmachen von emotionalen Eindrücken. Andy Dunhill hat sie beeindruckt. Ihm hat Felicia ein Buch gewidmet mit Frottagen. Das Wort Frottage kommt aus dem Französischen von frotter – reiben. Ein Verfahren, das Max Ernst ab 1925 entdeckt und entwickelt hat. Bei der Frottage wird die Oberflächenstruktur eines Gegenstandes oder Materials durch Reiben mit Hilfe eines Stifts auf ein aufgelegtes Papier übertragen. Die Frottage ist ein künstlerisches Stilmittel zur Integration vorgefundener Strukturen.

Andy war ebenfalls Künstler, Bildhauer und Zeichner. Wir waren zusammen in Spetzgart, bei dem Künstleraustausch Salem2Salem, bei dem sich jeden Sommer deutsche und amerikanische Künstler und Künstlerinnen treffen, mal in Schloss Salem, mal in Salem Art Works im Staat New York. Felicia kannte Andy schon länger, von Amerika, von der Arbeit im Franconia Sculpture Park. Ich habe ihn erst in Spetzgart kennengelernt und war beeindruckt von seiner Ausdruckskraft. Er arbeitete mit schwarzer Tusche und heftete die Skizzen, die in rascher Folge entstanden, an die Wände seines Zimmers.

Ich sah sie durch das offene Fenster, sah ihn am Schreibtisch sitzen und zeichnen, und dachte: Wow! Da ist ein neuer Picasso. Geballte Kraft, geballte Fäuste, Pommes und lästige Fliegen, seine Skizzen verrieten großes Können, elementare Kraft und: Humor. Er war Brite und kam nach Amerika, weil Obama gewählt worden war. Für Felicia war er ein Künstlerkollege, dessen Urteil aufrichtig war. Wenn er etwas sagte, war das eine honest critic, eine ehrliche Meinung, er nahm kein Blatt vor den Mund.

Sein Tod war ein Schlag. Sein Vermächtnis ist seine Kunst. Und seine Art zu arbeiten: Mit Kraft, Können und Humor. Mit der Frottage als Stilmittel zur Integration anderer Strukturen thematisiert Felicia Einfluss und Eindruck durch andere Menschen.

Was beeindruckt uns?

Wer beeindruckt uns? Was geht unter die Haut?

Der Philosoph Schelling schrieb vor 200 Jahren, dass sich bewusste Tätigkeit mit einer bewusstlosen Kraft verbinden muß, damit ein Kunstwerk entsteht.

Felicia arbeitet immer wieder mit Traumbildern und Tagebuchnotizen. Zeichnet Buchstaben und Wörter aus diesen Traumbildern in die Farbe, die sie auf die Kartons aufträgt, bevor sie Abdrücke macht.

Eine Serie von Trashquilts hat sie Tête du Travers genannt. Tête du Travers ist der Name des Bergs, gegen den ein Pilot 2015 ein Flugzeug mit 149 Passagieren gesteuert hat. Tête heißt Kopf. Le travers ist der Fehler oder die Quere. Esprit de travers bedeutet Querköpfigkeit. Gegen einen Berg mit dem Namen Querkopf hat ein Querkopf ein Flugzeug gelenkt und viele Menschen mit sich in den Tod gerissen.

Was ist im Kopf des Piloten vorgegangen?

Fünf Tage später schrieb Felicia unter dem Eindruck des Absturzes einen Text. Teile dieses Textes tauchen auf ihren Trashquilt Prints auf.

Kann dieser Vorgang zu einer Allegorie für unser eigenes Verhalten werden? Was geht in unseren Köpfen vor, wenn wir durch unseren Konsum, den hemmungslosen Verbrauch von Rohstoffen andere Menschen, andere Generationen schaden?

Für Felicia hat sich der Unfall am Tête du Travers verbunden mit der Wahlkampagne von Trump. Sein Verhalten ähnelt dem Verhalten des kranken Piloten. Der eine hat ein Flugzeug gegen einen Berg gelenkt, der andere ist dabei, ein ganzes Land gegen die Wand zu fahren. Und die halbe Welt.

Seine Worte: Trashtalk. Lügen, schön verpackt.

Believe me. Trust me.

Der Gegensatz von der Selbstdarstellung dieses Angebers und einem einfachen Leben im Wald ist groß. „Walden“ heißt das Buch von Thoreau, das zu einem Kultbuch geworden ist. Darin ist auch die Rede, heißt es: „Wozu diese verzweifelte Jagd nach Erfolg, noch dazu in so waghalsigen Unternehmungen? Wenn ein Mann nicht Schritt hält mit seinen Kameraden, dann vielleicht deshalb, weil er einen anderen Trommler hört. Lasst ihn zu der Musik marschieren, die er hört.“

Künstler folgen ihren Eingebungen. Sie ermutigen andere durch ihre Kunst, zu hören, was in ihnen laut wird, wenn sie allein und ganz still sind. Wenn sie im Wald sind. Oder am See entlang gehen. Am Oberen See bei Duluth. Oder am Bodensee.

Die Winter in Duluth sind kalt. So kalt, dass der Obere See zufriert. Es gibt Filme, in denen man sieht, wie sich das Eis aus dem See aufs Land bewegt. Knirschend bedroht es Häuser und Menschen. Natur ist bedrohlich. Kann bedrohlich sein. Bedrohlich wie Menschen. Bedrohlich wie ihre Worte.

Felicia hat Bricks aus Metall und Papier gemacht, mit denen sich Mauern errichten lassen. Aber sie hat keine Mauer gebaut. Die Bricks liegen in einem Haufen auf der Bühne. Bruchstücke einer abgrenzenden Haltung, der Felicia etwas anderes entgegensetzt: Den tänzerischen Schwung, mit dem sie Grafitstifte über die Papierbahnen führt. Damit bringt sie eine andere Energie zum Ausdruck, fegt das Starre, Erstarrte, Eisige und Vereiste weg, das sich in den letzten Jahren in der amerikanischen Politik ausgedrückt hat.

Im Sommer 2019 hat Felicia in Salem mit Kassandra gearbeitet. Eine Serie beeindruckender Bilder ist entstanden. Kassandra kam aus Troja und hat vor dem Untergang ihrer Stadt gewarnt. Und wurde doch nicht gehört. In ihre Kassandra-Bilder hat Felicia Schlagzeilen und Artikel über Amerika unter der unberechenbaren Führung durch Trump eingearbeitet.

Und sie hat das Motiv des kippenden Hauses entwickelt, ebenfalls nach einem Traum, in dem sie die Worte hörte, shore it up! Das Haus muss gestützt werden! Das Haus kann als Symbol für Amerika und seine aktuelle Regierung verstanden werden, aber auch für unseren Planeten.

Kurz vor dem ersten Weltkrieg hat Jan van Hoddis das Gedicht Weltende geschrieben:

Dem Bürger fliegt vom spitzen Kopf der Hut,

In allen Lüften hallt es wie Geschrei.

Dachdecker stürzen ab und gehn entzwei

Und an den Küsten – liest man – steigt die Flut.

Der Sturm ist da, die wilden Meere hupfen

An Land, um dicke Dämme zu zerdrücken.

Die meisten Menschen haben einen Schnupfen.

Die Eisenbahnen fallen von den Brücken.

Jan van Hoddis verbindet mit leichter Hand Banales und Apokalyptisches. Den Schnupfen und das Gefühl einer existenzielle Bedrohung. Es ist ihm gelungen, ein Bild zu schaffen für seine Zeit. Danach suchen wir, wenn wir Kunst machen. Und betrachten. Wir suchen nach einem Ausdruck für das, was uns unter die Haut geht. Felicia zeigt uns in dieser Ausstellung, was sie umtreibt, was sie beeinflusst und beeindruckt hat. Lassen Sie sich beeindrucken!

Katrin Seglitz

Speech for the vernissage of the exhibition “Impression/Abdruck” by Felicia Glidden on 17.1.2020

at the Kunsthaus Caserne in Friedrichshafen Fallenbrunnen

When you come into this room, you are impressed by the large-format works hanging here. Impression/Printing is what Felicia called the exhibition, and both words have a courtyard of meaning: In Impression, we hear the press, pressing, printing, pressing and pressing and pressing. Terms that have to do with printing and printing processes. And the question of what makes an impression.

This is the question Felicia asks herself, this is the question she pursues experimentally with her works, the question of what impresses her, impresses her so much that she has to look for an expression for it.

She grew up in Minneapolis and lived in the city until she was 18. After that she went to Duluth to study. She studied math and engineering and took courses in visual art and dance. Duluth is located at the Upper Lake, one of the three huge lakes in the north of the USA, on the border with Canada.

Duluth has a large harbour, from here ships sail across the St. Lawrence Seaway into the Atlantic Ocean. Raw materials are shipped in Duluth: iron ore, grain, coal, oil and wood. The city itself, with 86,000 inhabitants, is not a large city, only slightly larger than Friedrichshafen.

In her 3rd year of study Felicia turned completely to art.

She moved into an old wooden house in the middle of the forest, near the lake, one hour from Duluth. She set up a studio in the garage, heated with wood, made art and earned the money she needed to live by renovating houses and boats. She has lived in and with nature, an experience that she still carries today.

And shapes.

Which brings us back to printing and the impression that something leaves behind. Even before she got to know waste separation in Germany, she separated garbage when she lived in the forest. For the past two years, packaging has become more and more the focus of her attention.

Packaging is also designed and produced. They serve to protect food and products. Are opened or torn open, torn down and removed. They have a serving function, are usually overlooked.

Felicia makes them visible by unfolding cardboard boxes, placing them under paper and rubbing them with graphite to create an imprint. She has sewn unfolded cardboard boxes and packaging together. And made trash quilts from plastic bags.

In the beginning, the discovery of the production of plastics was celebrated. The success led to mass production. For a long time, we have felt oppressed and threatened by the flood of plastic in every conceivable form.

And yet there are plastics that we wish would survive us. In 1856, celluloid was developed, and from 1870 it was marketed and further developed as a carrier material for films. In 1951, production was discontinued because celluloid is highly inflammable. In a dry environment, the water content decreases and celluloid becomes an explosive that can ignite spontaneously.

Celluloid was replaced by a transparent film of tri-acetate or polyester coated with a photo emulsion. Stripes from the age of analogue photography can still be found in many households. Also with Felicia.

When the cellar of Felicia and Alain was flooded during a flood, it became clear that tri-acetate and polyester also spoil when it gets wet. The slides in her archive show not only the captured moments but also abstract landscapes of spreading mould. Felicia has made a memory skin from the destroyed photos, a memory skin. And turned them into an allegory …of impermanence.

Felicia: “Time is like a flood that covers and bleaches out what was once present.”

Plastics are used for packaging, for protecting things, but also as carriers of memories. In this exhibition, Felicia is concerned with making their materiality visible and the forms that are in circulation.

This is one aspect, one part of her works exhibited here. The other aspect is the making visible of emotional impressions. Andy Dunhill impressed her. Felicia dedicated a book to him with frottages. The word frottage comes from the French word frotter – to rub. A procedure that Max Ernst discovered and developed from 1925 onwards. In frottage, the surface structure of an object or material is transferred to a piece of paper by rubbing it with a pencil. Frottage is an artistic stylistic device for the integration of found structures.

Andy was also an artist, sculptor and draftsman. We were together in Spetzgart, at the artist exchange Salem2Salem, where German and American artists meet every summer, sometimes in Salem Castle, sometimes in Salem Art Works in New York State. Felicia had known Andy for a long time, from America, from the work at Franconia Sculpture Park. I only met him in Spetzgart and was impressed by his expressiveness. He worked with black ink and pinned the sketches, which were created in rapid succession, to the walls of his room.

I looked at them through the open window, saw him sitting at his desk and drawing, and thought “Wow! There’s a new Picasso. Concentrated power, clenched fists, chips and annoying flies, his sketches revealed great skill, elemental strength and: humor. He was British and came to America because Obama had been elected. For Felicia, he was a fellow artist whose judgment was sincere. When he said something, it was an honest critic, an honest opinion, he did not mince his words.

His death was a blow. His legacy is his art. And his way of working: With strength, skill and humor. Using frottage as a stylistic device to integrate other structures, Felicia thematizes influence and impressions by other people.

What impresses us?

Who impresses us? What gets under your skin?

The philosopher Schelling wrote 200 years ago that conscious activity must combine with an unconscious power in order to create a work of art.

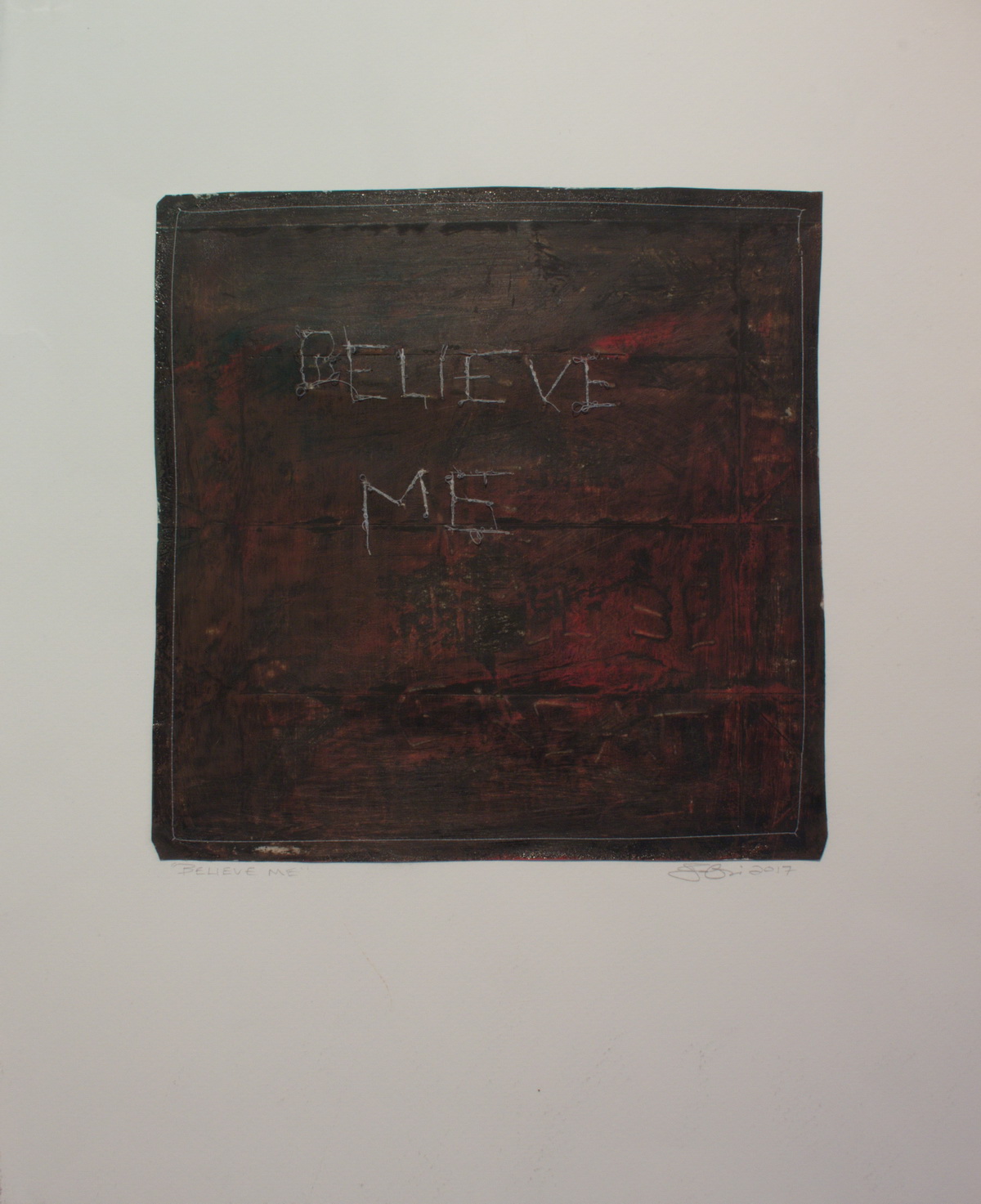

Felicia always works with dream images and diary notes. Draws letters and words from these dream pictures in the paint she applies to the cardboard boxes before making prints.

She has called a series of trash quilts Tête du Travers. Tête du Travers is the name of the mountain against which a pilot piloted a plane with 149 passengers in 2015. Tête means head. Le travers is the mistake or the cross. Esprit de travers means head. Against a mountain called Querkopf, a Querkopf steered an airplane and took many people with him to his death.

What was going on in the pilot’s head?

Five days later, under the impression of the crash, Felicia wrote a text. Parts of this text appear on her trash quilt prints.

Can this process become an allegory for our own behaviour? What goes on in our heads when we harm other people, other generations, through our consumption, the unrestrained consumption of raw materials?

For Felicia, the accident at the Tête du Travers has become linked to Trump’s election campaign. His behaviour is similar to that of the sick pilot. One has steered a plane into a mountain, another is about to drive a whole country into a wall. And half the world.

His words: trash talk. Lies, nicely packed.

Believe me. Trust me.

The contrast between the self-expression of this show-off and a simple life in the woods is great. “Walden” is the name of Thoreau’s book, which has become a cult book has become. It also says: “Why this desperate pursuit of success, especially in such daring ventures? If a man cannot keep up with his comrades, it is perhaps because he hears another drummer. Let him march to the music he hears.”

Artists follow their intuition. They encourage others through their art to hear what becomes loud in them when they are alone and silent. When they are in the forest. Or walking along the lake. By the Upper Lake near Duluth. Or by Lake Constance.

The winters in Duluth are cold. So cold that the Upper Lake freezes over. There are movies that show the ice moving from the lake to the land. It crunches, threatening houses and people. Nature is threatening. It can be threatening. Threatening like people. Threatening like their words.

Felicia has made bricks of metal and paper that can be used to build walls. But she didn’t build a wall. The bricks are in a pile on the stage. Fragments of a demarcating attitude that Felicia counters with something else: …the dancing movement she uses to run graphite pencils across the paper. In doing so, she expresses a different energy, sweeping away the rigidity, congealment, iciness and icing that has been expressed in American politics in recent years.

In the summer of 2019, Felicia worked with Cassandra in Salem. A series of impressive pictures has been created. Kassandra came from Troy and warned of the downfall of her city. And yet she was not heard. In her Cassandra pictures, Felicia has incorporated headlines and articles about America under the unpredictable leadership of Trump.

And she has developed the motif of the tilting house, also after a dream in which she heard the words, shore it up! The house must be supported! The house can be understood as a symbol for America and its current government, but also for our planet.

Shortly before the First World War, Jan van Hoddis wrote the poem Weltende:

The citizen’s hat flies off the pointy head,

The air is filled with the sound of screaming.

Roofers crash and split

And on the coasts – one reads – the tide is rising.

The storm is here, the wild seas are honking

Ashore to crush big dams.

Most people have a cold.

Railroads fall off bridges.

Jan van Hoddis combines the banal and the apocalyptic with a light hand. The sniffles and the feeling of an existential threat. He has succeeded in creating an image for his time. This is what we look for when we make art. And we look at it. We look for an expression for what gets under our skin. In this exhibition, Felicia shows us what drives her, what has influenced and impressed her. Let yourself be impressed!

translated with Deepl